I hope this isn’t the end, but it kind of feels that way.

It’s January 1st, almost the 2nd, 2019.

It’s so cold outside, a staggering cold. My breath hangs in the dark air like a ghost next to me. The frozen earth cracking and crunching beneath my feet as I walk back into the hospital from seeing the last family member leave.

It was finally quiet in the heart of that hospital. The clicks and clanks and beeps and hisses of an ICU settle into a soft whir. A cart rolls towards me or away from, I can’t tell anymore. No one smiles at me. After enough back and forth, the staff kinda knows why you’re there. You get the pursed-mouth, slight nod of approval they give all the people who are watching someone die.

The past several hours were a wet mess of tears and hugs. Family I haven’t seen. Family I hadn’t wanted. Friends I don’t know. Not enough friends. Not enough family.

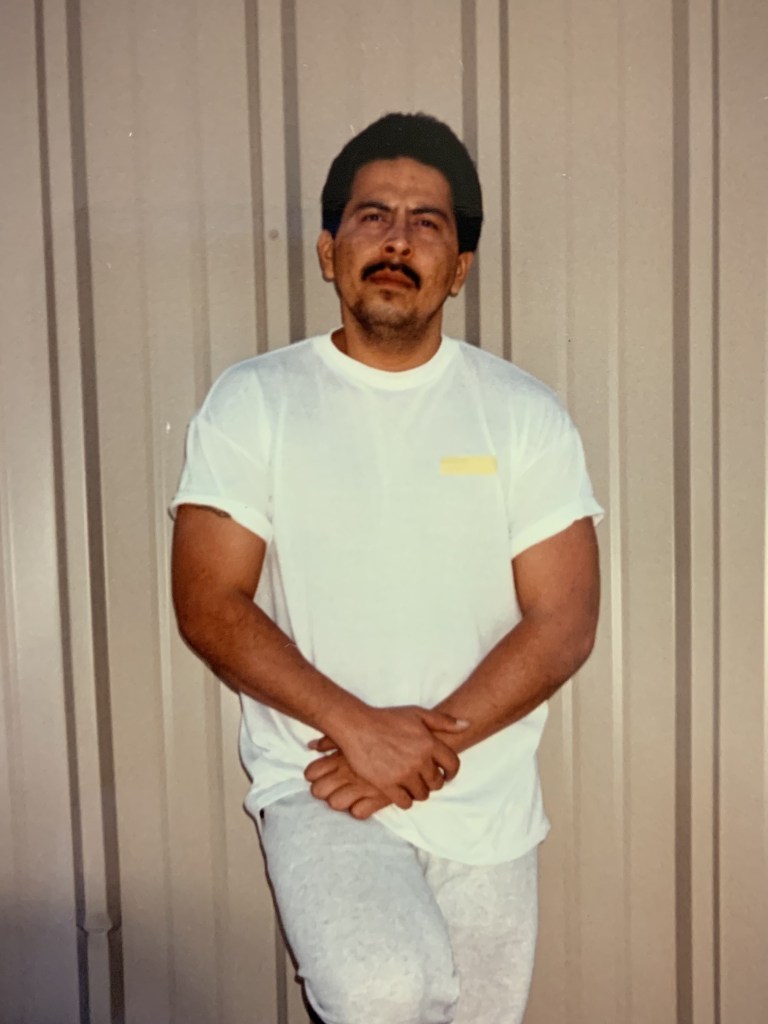

A few rooms away from the headquarters I had made with the ugly chairs and broken vending machines, my father is dying.

His tired body stuffed full of tubes and hoses. A Jackson Pollock painting of tape and cables and gauze. He is Autumn Rhythm, only painted in blood reds and hospital linen-blues. His chest heaving in a slow violence; surging with the air of the ventilator stuffed down his throat. A symphony of electronics hum and hiss and sigh behind him. Busy bodies in scrubs press buttons and inject fluid and medicines. None of it does anything more than prolong the evening.

For most of the night, we teeter-totter back and forth from hope to despair. I shuttle the family back and forth from the waiting room to his room in the ICU. A house-of-mirrors made up of glass doors and curtains. The nurse rolls his eyes as I guide another tour around his bed. The tears flow. Hugs exchanged. Onto the next group. At one point later that evening, his second nurse remarks to me “you know, most of what ICU is, is really just a chance for family to say goodbye”.

This is the most direct truth I’ve heard all night.

The bulk of the evening is more ping-ponging from the waiting room to bedside just in case they lose control and he spirals into this impending end. There are moments when the optimism is so high, I scoff at comments his friends are making, that we would eventually lose him.

How dare they… We would laugh about that later, I thought to myself .

Many other moments are razors-edge seconds of intense busyness around him. Family flies in to circle his carcass. Family flies back out. Useless prayers, for literally only god knows what. Between the groups, I am left alone in an off-white purgatory. To think, to scratch notes onto napkins, text, call, and answer the media-like questions of people that knew him. Occasionally, someone would pop out and walk me through some status update, or some procedure or change in the care he was receiving. Each time, it was with great urgency, the kind of urgency that one expects from this particular function of the hospital.

Eventually a doctor comes out and sits next to me. He takes a deep breath and without so much as an introduction or handshake says “Felix, varices are enlarged veins in and around the esophagus that carry blood. Over a lifetime of alcoholism, these will swell and become inflamed and eventually burst. That’s what’s happening right now. That’s what brought your dad here. We placed a balloon of sorts that inflated in his throat and the pressure is the only thing keeping him from bleeding out too fast. We would like to remove this balloon and see if we can quickly find and fix the leak. Do you give us consent to do this?”

There was an interesting feeling that I never had with my dad before. This time I was in charge of him. I could decide what happened. The doctor looked at me and waited for an answer, as if there was a chance in hell that I would disagree or even suggest an alternative approach.

I quickly agreed, and the doctor hurriedly left to huddle his team and run this play. I waited for about an hour in the purgatory waiting room. The clock ticked hard, chiseling away at the hour he said it would take.

The last time they called me over is different. I read a note of resignation across their faces.

There is no more rush.

I stand up, in what feels like slow motion, to be carefully walked over to the team of medical professionals and be informed of our entrance into this new phase of the process. The moment is thick with this i-can’t-believe-this-is-the-end- feeling that I still can’t name.

As humans, we tend to believe that our own moments are the most profound and the most meaningful. Like time should slow down and a shaft of yellow, Rembrandt-esque light would beam down and the cherubs would drape him in a dark maroon cloth. My brain believes that the memory should reflect that renaissance-type agony I was feeling, but in the back of my mind I knew that in just a couple short hours, there would be another family here, huddled around their own broken heap of memories and wistfulness, and, like most of the insignificance we wrap with prose, the agony reads wonderfully, yet It’s probably only meaningful for me.

They ask to talk outside the room, as if he couldn’t be involved in such a big decision regarding his life, or, not like it mattered because he was heavily sedated. Perhaps this, like many other moments during his life, it took a professional and an adult to decide what to do next. A sort of, go-sit-in-the-truck-and-don’t-touch-the-knobs moment. They said additional efforts would return less and less results and, in a matter of hours, we would be at the threshold of the same decision. Would I like to sustain these efforts, or let him go, they asked. The weight of it was lost on me at the moment. It seemed almost cruel to continue, but I also didn’t want to be the one to make the final call.

I decided to let him go.

There was more preparation to be done before we could actually set him off to drift away. The nurses prepared him via the tangles of artificial arteries and apparatus laid on and above and across him. The room is tidied up. Blood is wiped from surfaces. Like the crew preparing a stage for this, his final act. A single chair is placed next to the bed for me to sit. I take my place as the star of this drama. They leave. The curtain is drawn.

The life/death scoreboard of instrument monitors tick down slowly. His heart thumps hard but slow. So much less of what it is sending is coming back.

Respirations slow.

The violent chug of the respirator slows to a crawl.

His head turns slightly to his right side. Eyes half opened. Mouth agape. Tiny splatters of blood speckle every surface in there. There was so little dignity there.

There must be some poetic link in the fact that I am watching the death of the man that watched my birth, I just can’t make it yet.

His skin is cool and soft. And without as much as a delicate pause, he’s gone.

I held hand as he passed away.

The staff excuse themselves to give us a moment. Nothing moves. Not a twitch. Regret bubbles up from somewhere deep in me. I choke out something resembling crying. Anger. Fear. Sadness. Shock, all stutter out of me like a typewriter. I don’t know what I’m doing. I don’t know why it’s only me in there making all these decisions.

For a moment, the beep of his heart monitor flutters back to life. A strange, surprised relief hits me. The nurse steps back and very quickly works to assure me that this is normal. This is simply “residual electrical activity”, and “to be clear”, he is not coming back. (That tickle of excitement when I saw the flutter would come to reappear in my dreams for months afterward).

Internally, I’m spiraling into an anxiety attack. Outward, I’m calm. Collected.

A muted voice of a nurse tunnels into my breakdown to ask me questions. My words swim up through the chaos and break the surface. I try to sound certain and resolved, but I’m spiraling, hard.

Yes. Of course, I’m ready to talk about our next steps.

Yes, I would like a bottle of water.

Indeed, he is in a better place.

Yes. I’d be happy to finish the paperwork in another room.

The spirit of this moment rises off the bed and reaches deep into me, pulling hard at memories and traumas I had long forgotten. A warm, anxious, flashback to the previous March. Lying in bed, watching television and staring into my phone. My daughters are asleep in their rooms. Normalcy colors the walls here. My father tells me via text that I am dead to him. That he never really felt at home around me, “especially lately”. I’m firing the vitriol right back. It’s mad. Fast. Hateful. An argument that stemmed from some earlier issue which, as always, started with me asking whether or not he had been drinking. This time, however, was somewhat rare. In the past, we would go for a while without talking, but we would never leave on such a hateful note. Rarely did we bring out this level of animosity, yet here we were. The depths of his anger had been getting deeper and deeper, each time that he binged. The words he chose, the actions he chose to take, all were pointing towards something more severe coming. His words were becoming ominous, almost threatening. Not to me, but to my mom.

Over the previous couple years, which at the time I would measure in these binges, I had started to consider a few things about what I would tolerate and take part in as it related to his behavior. Me being a father of girls, how could I abide this and continue being this normal, engaged, person with him, when I knew what he was saying and doing to my mother? After all that she and I had been through together, anything alleged against her felt like a stab against me. Stupidly, I chose to engage him while he was drinking and that’s what started this raging dumpster fire.

We don’t talk again for over a year, and it’s the longest we’ve ever gone without talking. Even during the years that he was in prison. There were times that he would reach out again, still drinking, and I would respond with something mean or cold. There were many, many, fights kind of like this, but this one was different. I felt such a profound sense of “fuck it” this time. I still can’t explain why, but I just wanted to be done with it all. I had a world of excuses, that I was busy, or that it was time for me to focus on my family. Truth be told, I was scared to confront him.

Reality pulls me back to the hospital. Literally just minutes ago, we were still hoping. The “stabilizing” card was still in play. A series of specialists were paraded up to me to offer their plan in sequence. To be honest, I was more impressed with their process than their message. The effort and coordination of so many good people made me feel this false sense of relief. That there was no way he could possibly die with such attention surrounding him. But he still did.

Much like the rest of his life, his actions would develop in stark contrast to the support of the people around him, and yet again, he would reap the results borne from those actions, no matter the outcome.

People talk often at memorials and in eulogies of how someone “lived life on their own terms” but that’s bullshit. They live their life on life’s terms. We all do. And there are very few exceptions. We work shitty jobs and wake up early and fight shitty traffic. We pay bills and argue with our spouses. We cut our lawns and pay for our kid’s braces. Some more humorous people can take a step back and recognize the cycle and perhaps poke some fun at it, and for this, we will eventually memorialize them as having “lived life on their own terms” but at the end of the day, the terms are not ours, they’re usually someone else’s.

My father was an exception. He did exactly what he wanted, whenever he wanted and almost always at a cost to himself or those around him. See, living life “on your own terms” isn’t glamorous. It isn’t some wild and passionate, devil-may-care lifestyle. It’s hard and dark and gritty. It’s frequently punctuated with profound sadness and stark misery. It takes a resolve of steel. Not a resolve to accomplish something, or create something, but to lose it all. Over and over. A constant stream of apologies and reliance on the vastness of love to forgive once again. And we did. Because we loved him.

Living on your own terms meant giving up something of someone else’s. Usually, the ones that are closest to you. A wife that depends on you to make the rent. A daughter that just wants her dad to take her to fucking dinner for her birthday. A son that waits up until 2 am for his dad to walk through the door, only to wake up on the couch the next morning, disappointed and alone.

Back in the hospital room. This will be the last time I see his body. His hair that looks like my hair. His fingers and his tattoos. Scars that I’ve remembered since I was kid. Some new ones, from the past few years that felt like I hadn’t really known him. His face wears a coat of black and white stubble. Still soft to the touch. I kiss his cold forehead and I apologize. Of the entire vastness of this concise language which I know how to speak, and all the emotions I have felt over the past few hours, or even the past few years or decades, all I managed to gurgle up is a stammering “I am so sorry, dad. For everything”.

And I still am. And I will always be.

Had I known that he was so close to death, or that for the past two years the clock was ticking, and time was running out, I would have done more. Reached out more. Yeah yeah. The same shit everyone says when someone dies.

I now find myself sitting across a table in a stifling hot room from a young hospital chaplain holding a list of mortuaries, organized by county.

Such convenience.

She leaves to call the company to whom he promised to donate some of his organs. I drift into a sleep-deprived, cry-induced moment of reflection.

Moments and memories and sounds and smells flood back and wash over me. Flashing onto the screen in the darkened theater of my mind. Broken into chapters. Some good. Some bad. Dotted every few years with a situation eerily similar to this. Me, sitting across a table from someone who is trying to explain to me some consequence of his actions and what it would mean moving forward. Some strange person detailing some new facet of the relationship that I will have with my dad.

When I was very young, after a particularly harsh berating and a firm denial, it was a parole board member, outlining how severe his crime was, and how early parole was out of the question.

As a preteen, it was a school counselor, asking me how I felt about “the divorce”. As if it was its own thing, or as if I could even define what “the marriage” was in the first place.

As a teenager, a “victim’s advocate”, carefully reiterating to my mother and me that we were nothing particularly special, as these things happen all the time. “You’d be surprised,” she said, at how often a man comes home and smashes out the windows in the back of his apartment and then fights the cops that came to arrest him.

Indeed, we were.

And now, as an adult man, a female chaplain, who is younger than me, explains the logistics and paperwork associated with the cessation of his life. Offering a canned version of comfort, which is delivered with 5 Star wait-staff precision. They play the script all the way through. Platitudes of how amazing he must have been. How proud. At one point, she asked what he would be thinking if he were here watching this mess alongside me.

“Probably that he doesn’t want to fucking die?” …

“I’m sorry, sir. I meant no offense”

The next few months are a blur of emotions and wonder. Staring into a vacuum of his absence and sorting through what it meant. Sometimes it was tears and sometimes it was anger, but it was always something. I wondered most often how we arrived at that moment. How a lifetime of chances to change a pattern ended with such a typical tale. And as much as I wanted to believe this pain and this shock were somehow new to me and therefore special, and deserving of a high quality of sympathy, I knew it wasn’t. There are thousands upon thousands of people who, like me, will open an envelope in their driveway and remove a death certificate that defines the cause of death, and perhaps, like me, that also bluntly sums up their life story: “complications from alcohol abuse”.

Fatherhood hit me hard. I felt this burning commitment to something that was so far beyond myself that I couldn’t really process it. When my first daughter was born, I remember feeling this stunned sense of disbelief, and to be honest, it took a while for all the overwhelming feelings of love and adoration to really settle in. I can still distinctly recall wondering why I didn’t immediately have those feelings, and as time marched on, they eventually arrived. As I reflect on the whole period, it reminds me now of those time when you cut yourself deeply or perhaps break a bone, and initially, you don’t feel it and shortly thereafter, it settles into you and quickly consumes you, like a fire.

The love I felt for my kids washed over me with a similar, all-consuming flood. I became focused on their safety and creating some sort of legacy for them. I worried about catastrophic events that I never cared for. I developed a deep fear of flying, or, more specifically, a fear of dying far away from them. Way before I knew who they were and who they would be. I hated traveling with just my wife, only because I worried about what would happen to them if we both died. Who would take them?

I say all of that to simply say this: My feelings for my children suddenly painted a contrast between me as a parent and him as a parent. To this day, I cannot go to sleep without checking on them. Seeing their tiny faces in their beds. Maybe sneaking a kiss on the cheek without waking them. I can recall many times as a boy that I would go weeks or months without seeing my dad. How could he not be hurting? How could he even sleep without knowing that I was okay? Did he love me less? Were his children just not as important to him as mine are to me?

I find it naïve and whiny to ask such silly questions. Of course, he loved me. A lot, I would imagine. I heard stories about how much he would brag about me. HE would usually tell me so, and often. So then, if I am to assume that he loved me as I love my own children, certainly there was something that would prevent him from being there. Some force that I couldn’t even imagine. Some ghost that pulled him hard away from things that he loved. He would escape its grip and crawl back, scratching his nails into the ground to make up for the time he lost, but eventually, the ghost would grab him again and pull him back.

I learned that he existed as many different people to many different people. After his funeral, when we sat and talked with friends and family, I heard story after story about a man that loved art and worked hard. Of a man that loved old music, of a man that could make anyone laugh. A builder. An artist. An occasionally violent drunk. A poet. A warrior. A man who frequently and methodically threw away every single fucking thing that mattered to him, over and over again. Stories about deaths and births and events so sad that you had to choke back the tears. Some were so happy that you couldn’t breathe through the laughter.

The service was nice, as they say. The chapel was so intimately familiar to me from the many funerals I have attended there I almost know the staff by name. I know where they keep the extra tissues. I know where they keep the mints. The layout of the parlor where you post photos of the departed. I know the same cadence of talk-song-talk-song-prayer-leave. I walk to the same lectern. I look into a similar sized crowd. I share memories, maybe a couple tears. We leave and continue with our life until some twist of fate puts us back in those same rooms and processes.

Almost to spite the cause of death of the man we were celebrating, the drinks began to roll.

Hugs, laughs, the usual. I leave early. I kiss my wife and kids and drive to the airport. I boarded an airplane. I am flying from a world with him into a world without. I take out my iPad to watch a movie and I think about the stories that I just heard.

I let my gaze fall out into the dark abyss we are flying through, and I imagined watching a movie that tells a story of this man, Big Fe, and his son, Little Fe. His life and his tales and during these events, the moments when his son went to bed hungry or lonely or scared or terrified of the violence and seeing those events help the audience make up their mind about the main character.

They decide that he is a fucking monster.

But before the credits roll, the film respools again and you are taken through some pivotal moments and see the same events from drastically different angles, and you realize that all of the anger and resentment and abandonment you believed he was intentionally laying upon his young son was actually the opposite. It wasn’t directed towards him at all. Just the emotional byproduct of a man who was spiraling out of control doing his best to navigate a fast, unfamiliar world. Grabbing onto anything he could. Eventually losing his grip.

The movie ends and the screen goes black, and you see only your reflection in the black glass, and you realize that maybe you had it backwards the whole time. Maybe you are actually the monster.

One response to “The End Is The Beginning.”

I hope this was as therapeutic to write as it was to read we all have our end of life stories some good some not so much it was a wonderful reed. it let me see a pice of your life the flex I have known is so well put together so super smart and talented never knowing the tribulations you have had I too had an alcoholic mom an i too look back on the snap shots of life we don’t get out of this a live make peace with it I would like to try this maybe it would easy my mind

LikeLike