Though I am sure there are more streets that have such a charm, one unique thing about 26th avenue is that at certain points, you can see the shimmer of downtown Denver from the plain old suburbs as the car you’re driving crests the high points in the road.

To me, this always felt like a periscope to something better than what I had. A chance to peep above the surface and see something beyond the fishbowl I was living in.

The road itself forms a neat artery from Applewood, which is west of Denver proper, into downtown, where it eventually hangs a sharp left and intersects with Speer boulevard.

In Wheat Ridge, sandwiched between the city and the tiny suburb, 26th creates the southern border of Crown Hill Park and cemetery. If you cut through the old neighborhoods with the big, beautiful cottonwood trees going north from Colfax, you would meet the silver chain link fence, just beyond that, a forest of marble and granite headstones, all of them similar in their uniqueness.

Only someone with the sentimentality of an 80’s baby living in the 90’s could appreciate the way it created (literally and figuratively), a road home from almost all points. You would have to have been born without an internet connection to understand the value of such a road.

Venturing into the new world west of what I had always known was tough, but 26th felt like a lighted runway home in the dark. It was the road my mom took to her new job. It was the road I walked to my new school. The house that my grandparents lived in was on 26th, just a mile or two down from us. Some of my new friends lived within a block or two of it. It became a tether that let me wander further and further, learning more about my new home and more about myself. Even to this day, sitting in the seat of a plane heading west, I can literally see the most of my life, at least the formative stuff, and it all happened along a short strip of asphalt labeled with just a number.

The independence that came with that was somewhat new to me. There was a naïveté in the air of Edgewater. I felt like danger was around every single corner in Denver, and it usually was. From kids just like me looking to make a name for themselves, or the older brothers of those kids, looking to slice me up or throw a couple stray rounds at us for walking through their block.

Explaining my apprehension to simple tasks like walking home or the caution I learned to exercise in the dark was funny to the new friends I had made. They thought I was paranoid. Better safe than sorry, I suppose.

My room in the apartment we had faced west and at night, I would open the aluminum sliding window and stare out into the sodium lamp-orange darkness at what I felt like was my future.

My first year of high school was unremarkable. I took the normal slate of courses one would expect of a freshman, I attempted to glom onto any clique that would accept me. I lusted after girls that I lamented about in bad poetry, having talked to exactly zero of them. I discovered AOL chat rooms on the public computer at Edgewater Library. I dressed in baggy clothes that transcended any particular subgenre of teenager and devoid of anything one could call “style”. I listened to the radio nonstop, and like most other kids my age, made a random genre of music my entire identity for a little while.

At the time, my dad was working at the janitorial company. When you’re young, you view anything your parents do with such reverence. He was a “general manager” of a company that cleaned office buildings, which in my mind was damn near a presidential level of responsibility. I would toss these words into conversation with my friends to make sure they knew how serious this job was.

I would go with my dad to their office, which had a small front-of-house office and a large warehouse with inventory of cleaning supplies tucked away in the back. There were several other employees that worked for my dad, all smokers, all old, all gross. They would gather at a picnic table in the back and complain bitterly about the owner who was a rather large, delightfully animated man named John. An east coast kinda guy if you’ve ever seen one. Slick talking, fast. Wheel and deal. You know the type. They would ask constantly about what I was going to do with my life. And staring in the face the future that these people chose eliminated at least one possible route.

There were jokes amongst the employees about the entire operation being a way for John to disguise some drug sales empire, but I think the truth was probably closer to him occasionally dabbling in some recreational cocaine, a theory that would be supported by hearing my dad sniffing in the bathroom every now and again during his benders while he was employed by the company.

Some weekends and during the summer, I was given a job to assist with the crews that would go and clean large offices for real estate companies, or accounting offices. One notable place was the Genesee headquarters of an air cargo company called Atlas Air, which as of this writing, was still operating, although in a different city.

I would get picked up around 6 pm, right after my mom fed me. A white van with the JL logo would pull up and honk. An older gentleman named Larry would be waiting, smoking, and listening to the Steve Miller band. To this day, I can still smell that van. The acrid stench of BO and cigarettes was enough to make me gag a few times. I would roll the window down all the way up the I-70 corridor, about an hour west of Edgewater. The air would almost always recirculate through the van and create this vortex that sent the smell right back in my face.

We would arrive at these big commercial buildings in the late-yet-light hours of summer. Unlocking closets and getting supplies, carting around a vacuum or trash can. The routine for most of the buildings was called “ash and trash”. Throw trash out, add new liners, dust the surfaces. Wipe handles. Long carpet would get a quick vacuum. Easy peasy.

One memorable night, I went up with my dad. We drove into the parking lot of one of the buildings to see one of his cleaners outside, hysterically crying. She ran up to the Jeep and told my dad that there was a dead guy in the hallway. He told her (and me) to stay in the Jeep, running inside to see what happened.

Naturally, I crept behind him into the building to take a look for myself. He walked fast through the lobby to a long narrow service corridor. I waited for a moment and then ran behind him. I stepped next to the hallway without stepping inside, imagining that I looked the way a SWAT officer would, prior to clearing a room. I stuck my head into the hall to see my dad standing and facing a heap of clothes and tools piled up awkwardly in the corner of the hall. A small step ladder beyond that, leaning against the wall. I could see the man’s shoe and ankle, bent unnaturally against the wall and the floors. I could see his hair, his head facing away from me. His cell phone was ringing nonstop. Creating an eerie alarm through the echo-ey corridor.

We went outside and my dad called the police. They showed up rather quickly, dutifully taking statements from the woman and my father. After about an hour, a cop came outside to tell us we could leave. My dad asked what happened. The cop said the man was an electrician. He grabbed his ladder and went to do some work above the dropped ceiling. Since the power was still on, his best guess was that the man tried to perform some work without shutting it off. Taking a small-voltage zap, he fell off the ladder, breaking his neck. He guessed it was probably just a few hours before.

We checked on a few other buildings and then left. The drive was quiet. My head was spinning. I couldn’t imagine who was on the end of the phone. Was it urgent? Were they worried? I wanted to know more.

I could tell that my dad was thinking about it. There was a weird apprehension in the air. My family has always struggled with how and what to say during these intense emotional moments. Rather than risk saying the wrong thing, most times they opted to say nothing at all. Leaving me to process complex emotions on my own.

Death was a complex and taboo subject around my house. Just a few years earlier, but back in the different world that was our duplex in Denver, a friend of my father’s, Dan, came over to have dinner with us. The details of this dinner are so clear to me, because unlike other nights from that era, this is the night I discovered death.

Now, to be clear, no one died. Not at my house, at least. But along with the stench of stale beer, sawdust and Marlboro Reds that Dan brought with him, he also brought a VHS copy of a movie called Faces Of Death. After the delightfully prepared cube steak that my mother prepared, we sat down a few feet away in the living room and started the movie.

The next hour and a half or so was a wild ride. Looking back on the footage now, it’s hard to take it seriously. Although there are very much parts and pieces that are real, the rest is so goofball-cheesy that it’s hard to take seriously the impact that it had on me. But for me, it wasn’t the death (or fake deaths) of the people that I saw on the screen as much as it was a cold steel wedge of reality that the people near me, the people that I knew and loved, would eventually die. And although I knew of death, the concept was painted for me without the deep black of finality that I had suddenly been shown.

The rest of the night was a paranoid half-sleep where I meticulously imagined the deaths of mom and my grandmother. Several nights after that, after a similar paranoia, I woke my mom up by pretending to have a loud nightmare. She came into my small room to see if I was okay. I described to her in depth, that I was worried about her and my grandmother dying; that I saw their funerals and their cold faces in crisp white caskets. I cried hard into her shoulder and eventually fell asleep. To this day, I don’t know what decision-making breakdown made my dad show me that movie,

Back to my night job, and despite the dead-guy thing, most other nights were actually pleasant. I made decent money wandering around buildings, listening to two or three tapes I had stuffed in my pockets on my Walkman. To be clear, I was living in the CD era, however, if you are old enough to recall, the first-gen Discman skipped like crazy unless you clicked the “skip protection” button, which if you know that, you would also know that it drained the batteries. And those weren’t the rechargeable kind. Tapes were cheaper and never skipped and were super easy to carry a couple of in your hideous fucking cargo pants. My favorite part of the evening was getting to go back to the office of a company called Atlas Air. They had an amazing break area with a soda fountain, and there were large model airplanes everywhere. Huge cargo 747’s with no windows, aimed skyward and heading towards nowhere. The scale of them was almost as grand as the real birds. The trademark hump, the large tail, emblazoned with the gold Atlas logo of the titan holding the earth but in a minimalist gold wireframe outline. The owner of the company had an office that looked more like a conference room. Large Persian rug that looked like a runway towards a gorgeous wooden executive desk. Airplanes, globes, and memorabilia of aviation adorned the shelves. It was magnificent. I felt like the brainless scarecrow, seeing the majesty of Oz. What could this man possibly do to require such luxe accommodations? I wasn’t sure, but I know that I wanted it. All of it.

The details of that office are hazier than I wish, but the feeling impressed upon me was heavy and deep. There was this magnetism in seeing someone create so much from nothing at all. I loved the perspective of it all. I wanted to see and know more about commerce. The exchange of dollars, the suits, the talking about numbers. It was all I could think about. I spent the summer in the same routine. As August rolled around, I went back to school and left that job and those people.

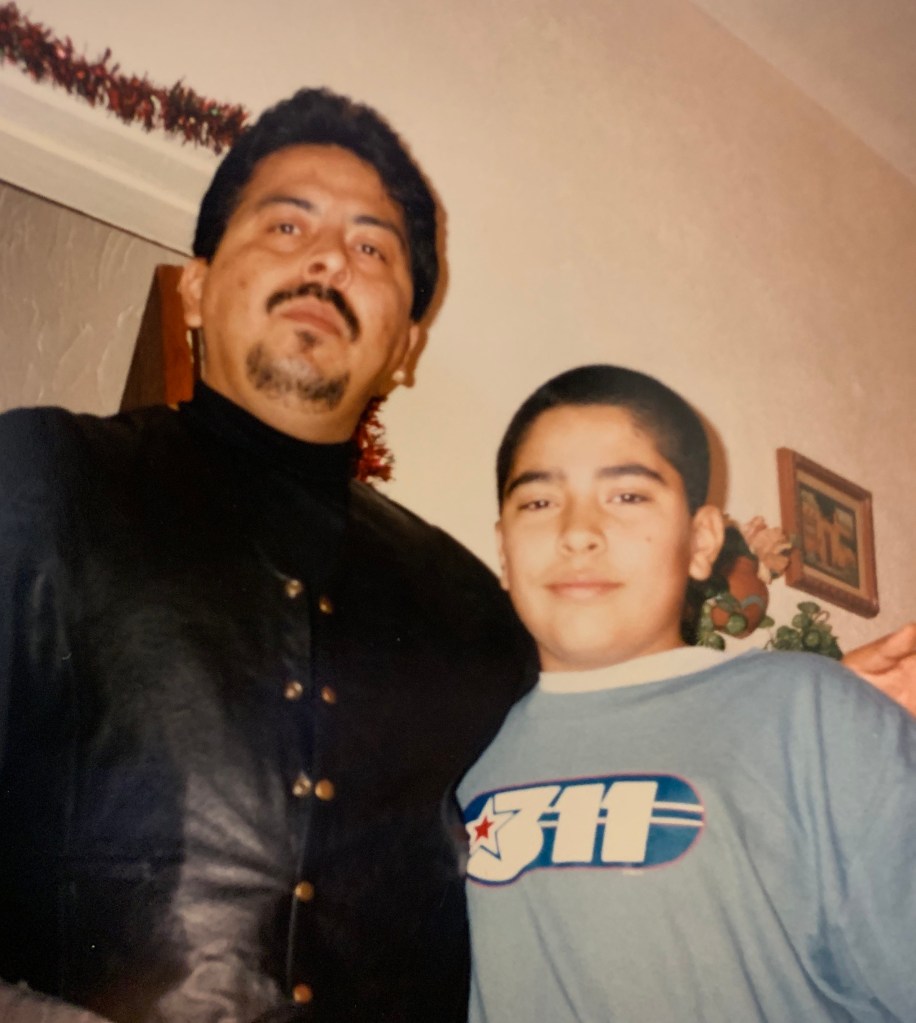

The Christmas of that year was one of the best in my life. Every year that my dad was home for Christmas, he was consumed with buying gifts for my sister and me. The weeks leading up to Christmas, he was stopping at the mall almost daily for new stuff. Sneaking things in the house under blankets, hiding gifts in the closet. Opening them would take so long that it would turn into a chore. The first few gifts, we would stop and carefully admire, showing it to the room before casting it aside for the next one. Wrapping paper would fall to the ground around us, creating an ocean of trash we would wade through, grabbing more and handing them out to on another. Clothes, toys, leather coats, chess sets, video game consoles, CD’s, jewelry.

During the holidays when my dad was sober, my parents would interact as two people in love, giving us a rare glimpse of them free from the normal level of irritation between them. To think of them now, as a couple of kids in their early 30’s doing their best to navigate adulthood and parenthood makes it easy to dull any criticism I may have for their parenting or the product of it.

People can hang any poor result on their parents, and many of them do, but the reality is that most everyone is just doing the best they can with what they have. My parents were no different.

In the first month of summer after I graduated high school, my mom and I sat together watching a movie. The phone rang and the other end was a party that I was invited to earlier in the week but declined. I said hello a few times and finally heard the voice of a couple friends, asking, or rather, telling me that they were on the way to get me. I said no and hung up. Sitting back down to finish the movie with my mom. Eventually, her curiosity got the best of her, and she asked who it was. I told her it was my friends wanting me to go with them.

My dad was gone, having left on a particularly harsh bender. As usual, there was a fight. But as I got older, I could see the pattern long before the clash. He would come home a little later each night. A year or so earlier, he quit the janitorial job, supplementing his income by working with an old friend from his time in prison. Together they worked on a crew framing houses. For everything he was and wasn’t, he was a hard worker.

I would get this feeling in my stomach that tonight would be the night that he just didn’t show up, or worse, he would come home drunk. The fighting would start, and the world would fall apart for a few weeks. No sleep, all worry. But sometimes he would eventually walk in, covered in mud and dust and I would feel terrible for not giving him the benefit of the doubt. Those times weren’t ever as frequent as I would have liked, but it did happen.

My mom didn’t want me to feel stuck at home with her. She was usually one to turn in early anyway, so a little gentle persuading and I called them back. About 30 minutes later, I was in a beat-up Honda driving off into the dark.

The night was a blur, as most of them are now. Some mix of restaurants, music, cigarettes, laughter. The Honda buzzed back down 26th avenue a few hours later. One of us sleeping in the back, two in the front talking about nothing at all.

The artery that was this road afforded the ability to see far in the distance. The apartment we lived in sat just a few feet from the edge of the road, giving me the unique luxury of seeing where I lived from very far away. As we crested one of the many hills along the road, I could see the unmistakable blue and red lights of law enforcement burning a colorful haze into the dark of the night.

I would imagine that when faced with the theater that is an emergency situation most people don’t assume they’re part of it. That was never the case for me. I always knew that the cops were there for me, or more likely, my family. Tonight was no different.

“I wonder what is happening up there” someone in the car muttered, but I already knew: my dad came home.

The car approached the colorful mess and slowed and without even allowing it to stop completely, I poured out of the passenger seat with a knot in my stomach and a suddenly dry mouth. Walking through the lot was like weaving through a showroom of emergency response vehicles. Police cars and ambulances, even a fire truck. I could see the unhiding faces of my neighbors staring out of their windows towards the spectacle of my family, the yellow light of their apartments making bright wedges against the dark of the brick apartment façade.

As I approached the door to my place, a very unwelcoming police officer with a severe bleached-blonde flat top stopped me. “You can’t go in there”, she said, placing a hand firmly against my chest. I reached past and pushed my way in, with her only stopping when I said “I fucking live here.”

In the brief moment, with the mess of “help” around me, and someone “guarding” me from entering my home, I couldn’t help but think that I was about to walk into only one outcome: that my father had killed my mother.

Walking in and seeing my mother on the couch was a relief unlike I had ever felt before, short-lived, however, because I knew something had still taken place here. My mom sat tiny and frail on the tan leather couch, sandwiched between two women. One was our landlord, the other I didn’t know.

I walked over quickly, hugging my mom and asking what happened. The woman I didn’t know introduced herself to me as a “victims advocate”. So now we were victims, and we needed this woman.

There’s a unique phenomenon that comes with growing up with someone as destructive as my father. There are constantly people involved in your life in some capacity intended as help. Injecting the cold administrative arm of the government in our lives was a reward for loving this man. This unremarkable woman was just the next in the line of people that we would be receiving unwanted “help” from. Moments when a place you only knew as a room of comfort or utility, like a living room or a kitchen suddenly became something else. Filled with people you don’t know. Using the same counter that your grandmother gently rolls tortillas on to fill out a contact report. The swish and crackle of velcro on utility belts filled with weapons and restraints against the soft of the cushions your mom places under your head when you’re home sick from school.

Follow-ups and circle backs, all the while doing as much as we could to make sure we seemed just fine to remove the probe of bureaucracy from our lives.

If you were to build the courage to grab your dad by the face and scream all the things that you hated about the things he did, you would never mention this, but this minor invasion of the places you didn’t think were sacred until you saw them severed and smeared with “help” was just another tug at the threads making up who you are. Of all the indignities, the injustices, the hurts and the bumps and the bruises you would present as evidence, this wouldn’t make the list, but oddly enough, when the bumps go away, and the bruises heal, these are the things you remember.

Not the blood, or the broken glass.

But the black of a police uniform juxtaposed against the honey almond floors in your grandmother’s dining room.

Sitting next to my mom on the couch, I was told the events of the evening that I missed. Not too long after I walked out of the door, he started calling the house. The message wasn’t important, but he made it clear he was coming home for either his stuff or for revenge. My mom made it clear that should he do that, the cops would be called, which incensed him. Not long after the calling stopped, he came home to a dark apartment, with the doors locked to whatever capacity they could be, and my mom hiding in the closet in my room. To this day, it pains me to imagine the fear she had while sitting there. It pains me more to know how much of her life she had devoted to this man only to find herself in such a terrible position, literally and figuratively, over, and over.

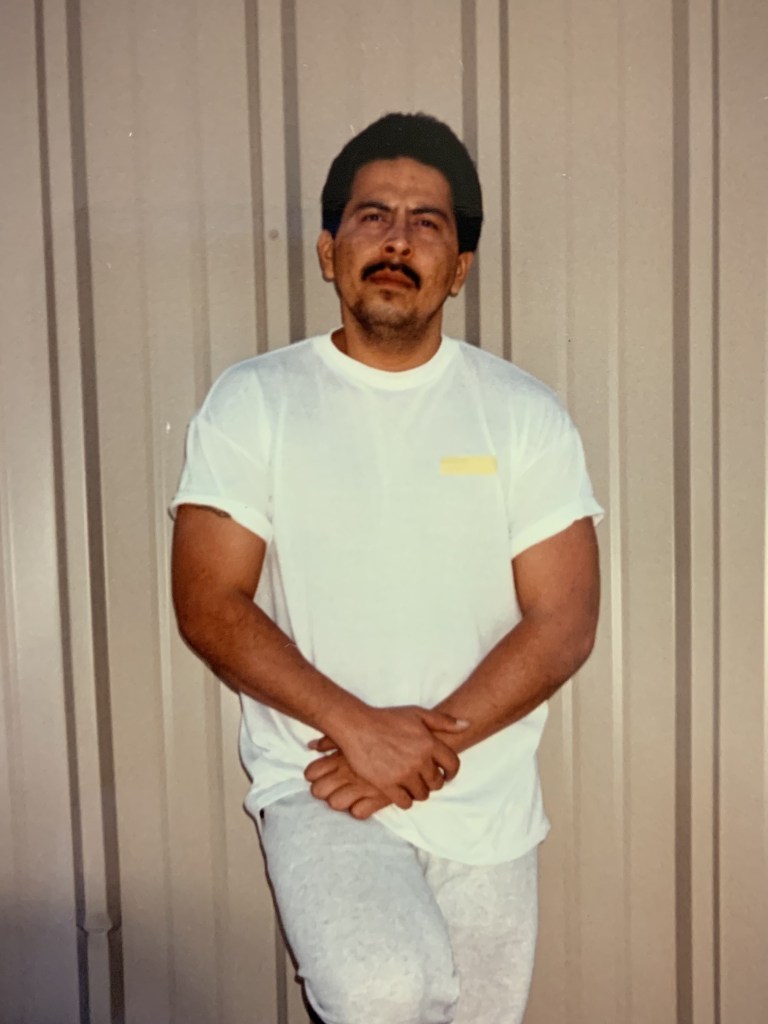

I imagine that him banging on the door was loud enough to immediately involve the neighbors, most of whom also made the decision to call the cops. As he realized that she wasn’t going to open the doors, he took his fists and began breaking the single-pane windows from the back of the apartment. The sound alone was enough to send my mom into a panic, calling the police again and again. About the time he was attempting to climb through, some of Edgewater’s finest were arriving on scene. Running up to the mess he was creating, shouting at him to stop, my father wheeled around and started swinging wildly towards the men. As most of us are aware, the police don’t take kindly to such things and these gentlemen dispatched him accordingly. Seeing him in jail a few days later, it was quite literally written on his face just how much they didn’t like that.

The aftermath of this event felt a little different. When the lights turned off and the helping and guarding and swarming subsided, it was just us again. A few hours previously we sat on these same couches, free of court dates and victims advocates. Free from the pity and anger of our neighbors who were dragged out into the cold night to watch our disaster unfold. We were now left to wipe up blood and sweep glass shards into the trash. Literally and figuratively picking up the pieces.

Although none of these episodes with my dad were ever anything to be proud of, this one had a particular air of humiliation to it. We had gone such a long time without unraveling, we were stupid enough to believe that maybe… just maybe, it was over with. That we could live and survive and even thrive as normal people. That we could be the people that worked hard all week, ate normal meals, went to bed at normal times, took short vacations always by car, walked the flea market on Sunday mornings, visited friends to watch the game, took walks after meals, saved money, didn’t hide bruises, didn’t lie about crying all night, didn’t have to clean one anothers blood from the floor, didn’t have to call parents at 3 in the morning to post bail, didn’t get the hinges of your doors ripped off by police executing a warrant, didn’t take an ambulance ride after OD’ing… But it couldn’t ever be that easy. We could never be those people. My dad always pulled us back in spectacular fashion.

The next few days were dotted with the uncomfortable interactions from friends and neighbors asking if we are okay.

What happened?

Where is he now?

Is your mom okay?

So on and so on. The anger in me saying to myself “it’s not their fucking business” and the shame in realizing that we made it their business.

After a few days, a letter arrives from the Jefferson County Department of Corrections, addressed to me but certainly written with the intention of her reading it. A preamble of superficial love. A hasty apology. A long list of the things he would need us to help with. Money, firstly.

This event was remarkable in that it was the first time that my mother let me make the decision as to whether I wanted to respond to him. I sat with it for a day or so and wrote back. I don’t recall what I actually wrote. It wasn’t particularly consequential, after all, what could I say? That it was okay? That I understood why he did it? I think I just told him about my new job, working graveyards at CoorsTek.

He responded quickly, asking for me to come visit him in the county jail. A few days later, on a rare day off, that’s what I did.

The Jefferson County detention center is a large six or seven story facility that looks like a set of handcuffs when viewed from above. The building is imposing. It has a presence to it that conveys the singular purpose of it. Walking in the building I see the slick glossy floors and row upon row of chairs. The lines in the floor draw your eyes toward a glass and steel cube housing two guards that are not in the mood for a teenager, inexperienced in the interactions that require such paperwork and proof of everything.

After getting my paperwork in order at the merciless inconvenience of the guards, I sit and wait. Visitors get to come up at certain times. I am early and I am required to wait about an hour for the next group to go up. A few more people file in, taking care of their sign-in and sitting near me. Together a large guard takes us to an elevator and in a few seconds, we are on the floor. Walking out of the elevators, I am led to a long hallway, on both sides, booths of concrete and steel with telephones against the wall. It’s exactly like every prison movie I have ever seen. The thought is somewhat amusing to me. I am told to go all the way to the end, and he will be on the left.

As I approach and turn, I see him there and whatever humor I had about the moment was stricken from me. The walls of gray and the large steel frame of the thick, scratched glass create a picture frame around the stark orange of his jumpsuit. He looks like a portrait painted on a sad gray canvas. His face swollen and bruised. His hands are black and blue and covered in cuts. Until that point, I hadn’t ever really felt sadness towards my dad. I usually hovered in the anger column of my feelings, but this was different. He was caught in the consequences of his actions. There was no escaping this. The devil that pulled at him caught him again.

This was the beginning of the era where I stopped seeing him as my father, and I started seeing as a son. Not my own, but as the child of someone. A baby boy, once held and revered as they always are, as something special and amazing. Someone who would change the world. Some tiny thing that you pray and hope and worry over. And here he is now, having not changed the world, but having reached a curious hand behind the curtains for a peek of a life less ordinary, and gotten pulled into the cogs and gears of a very unforgiving machine and spit out the other end, bloodied and battered.

Alcoholics have a talent for blaming other things and they only take credit when doing so makes them appear in control. I can recall in countless conversations overhearing my dad tell people that he decided he was done but neglecting to say that he was arrested or somehow unable to drink otherwise. Being one of the most charming men that I have ever met, there was always someone who believed what my dad said, and when the equilibrium in my own life was at stake, I usually did, too.

But here together, sitting in this fortress, with him wearing the bleeding cuts and bruises of his actions, with the stark-naked corpse of the truth laying here between us, what he mustered up was:

“You know I would never hurt your mom”.