I woke up in a bright room. Small. Smeared in the art and subculture of the mid 90’s. At every crease and corner, the overlap of boyhood and manhood. My collection of belongings spanning the gap of two eras in my life. Toys on shelves next to books of German philosophy. I still had some stuffed animals that my grandmother had given me, but I also had posters of half-naked Supermodels that I got at Spencer’s at the mall, purchased by the very same grandmother. Funny how that goes.

In the air, the unmistakable aroma of weed pressed its way through my closed door. The fan next to the bed buzzed and rattled the posters on the wall. I could feel the thump of bass reverberate through my bed. It was 9 am on a warm Christmas Eve, 1994, and I was pissed.

In the kitchen, my dad was busily cooking breakfast and smoking weed. Weed was a lifelong habit for my dad that somehow always flew under the radar of all the things he was occasionally abstaining from. California sober. The lesser of two, I suppose. I hated the smell of it as a kid. I still do. Waking up to it was worse than walking into the house after school and it smacking you in the face, but both were enough to make me irritable.

The bass from the stereo shook the cups on my nightstand.

Throughout my dad’s history of leaving us and then eventually coming back, the stereo was always there. He would leave, and then pawn or sell most of the belongings he could carry, and eventually he would return, and the first thing he would acquire when he moved back in was a new stereo. This stereo was the biggest that I can remember. A head component connected to massive speakers pumping music throughout the tiny duplex that he, my mother, and I lived in. Typical weekends would find her at work, and he and I lounging around, spanning decades of music, WAR, Led Zeppelin, The Isley Brothers, Van Halen, Eric Burdon and The Animals, Malo, Tower of Power, Metallica. Stacks and stacks of tapes and eventually CD’s of who’s music would eventually paint the background of my life.

I had a theory for a long time that as teenagers, we overvalued music. Placing way too much importance on what it actually did for us, but as I reflect now, at almost 40 years old, I couldn’t imagine my life without those songs, which so perfectly captured what I felt, or as it were, what I knew that I would feel someday, about someone or something.

Dad was making what he called a “wiglaoo”, which was essentially a casserole made of eggs, cheese, sausage and potatoes. He learned to make this in prison, is what he said.

Since he had only very recently been let out, there were a lot of stories and a lot of things that he learned in prison that he brought home for us. These random knacks and tricks for drawing or cooking gourmet meals with convenience store ingredients. How to make necklaces from unraveled sock threads. Ink made from ash. The convict origami of folding paper into an envelope. All of these were like magic tricks to my 12-year-old brain. Each and every one I would share with my friends at school as soon as I possibly could, to soak up a bit of the street cred that I thought came with having an ex-con father.

I still don’t know what it is that made that stuff seem so appealing. Was it the fact that most kids are just impressed with who their fathers are? Or was it the glitter-in-the-gutter that 90’s popular culture was beginning to embrace? I don’t know. When he was in prison, he would occasionally send home things he had created. Some random craft project that he had worked on. He would usually replicate designs or logos of things that I was currently into. Most recent, a small yellow stock card with the Mortal Kombat dragon logo on it. Handwritten greeting cards with his own amazing penmanship on display.

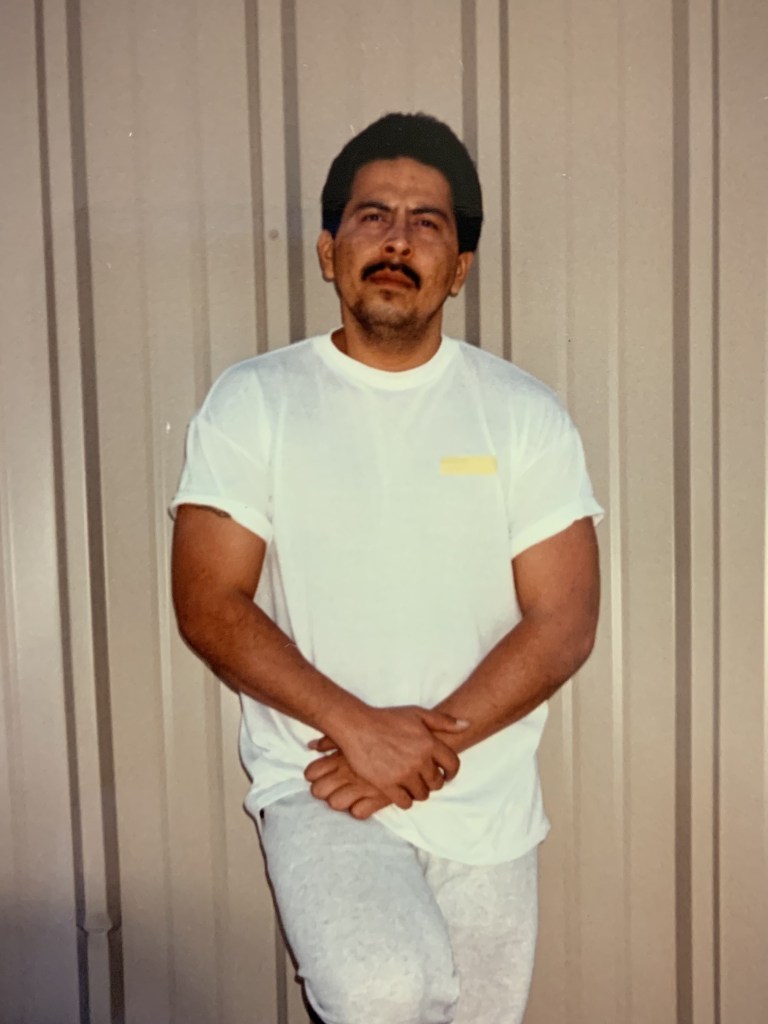

He came home with a wardrobe of white shirts with faded yellow patches on the chest that once had his Department of Corrections number on them. Red Kap Jackets and Dickies pants that had the unmistakable look of a recent prison release. All of which I clamored for immediately, and even though he was 6’ 2” and I was definitely not, I still wore them wherever I could and with an unusual pride.

My father was released on parole earlier that year and he was only let out provided he was leashed to a smattering of restrictions regarding work and alcohol consumption and God knows what else. Although the joy of having him at home was overwhelming, it was a radical change from the only-child life I was living. (Not actually an only child, I have a sister who is 2-ish years older than me, but who rarely lived with us.)

The only-child life existed between my mother and me. In the beginning, it was her and I. Dad would come home and reshape the dynamic to her and him, and then me. And eventually, when things fell apart, it was her and I that picked up the pieces together and continued to be a family. I always felt this tremendous sense of “welp” as we sat alone again, trying to pick up the pieces.

When he was gone, I had the run of the place. When we bought groceries, I got to pick everything. I stayed up until I wanted to go to sleep. I ate what I wanted and watched what I wanted. I was reaching the age where I was still excited for Christmas, but I didn’t want anyone to know. In my mind, I was certain of a great and many things, an expert on all-things music, an at-home Jeopardy champion, a professor of middle school sociology. In the real world, I was a scared little boy who was elated to finally have my father home. Him coming home ended the constant interaction I had with my mom. Sunup to sundown. They needed their time alone, watching movies or going to the store. I was left to my own to grow up and do young adult things.

I stumbled from the room and landed heavily on the couch. Before I could settle in, he called me over to the stove where he carved a huge slice of the monstrosity he cooked. We ate the wigaloo together and washed it down with Nestle chocolate milk. The powdered kind that came in a metal tin. The kind that you had to mix yourself. We typically read the paper together. Like a gray and gritty tablecloth, The Rocky Mountain News almost always covered the table at my house when my dad was home.

As we sat on the couch after gorging ourselves, he said “Get ready Gato. let’s go see your uncle Gerald”. I can still recall the pit-feeling in my stomach from each and every time we had to go see him.

As I sit here writing this, I realize that there are many things about my father and our life together that I have never actually verbalized, certainly not to him. Here is one: As a child, I hated my uncle Gerald. He was a degenerate alcoholic, who, from the stories I have heard, was violent and abusive to everyone around him, especially my father and those closest to him. Of the many times we visited him, it was never at the same place. Usually, some squalid apartment that had the unmistakable odor of beer in the carpet. Like a party house, where the spills were perhaps dabbed with something, but never really cleaned. He usually wore a black leather newsboy cap. Missing teeth. The burning hot alcoholic breath.

Every time I saw him, he was bubbling with the very specific euphoria of a drunk who hasn’t seen you in a while.

You know the kind.

Poking at me. Teasing. Cheek-squeezing. The stereotypical interaction we’ve all had with an old aunt or uncle “I haven’t seen you since…” or “why don’t you ever come see us!?” and the ever-present “you think you’re too good for me?” The answer to that last one always flashed in my head like a Hollywood marquis surrounded by burning-hot white lights: “Abso! Fucking! lutely!”.

Gerald was a disaster. Always. He met the same fate my father did, just about two decades earlier and with far less lamentation from family, I would guess. Certainly, from me.

I remember leaving my high school photo class to attend his funeral. A state-paid service in the cold, rainy part of Spring. He arrived in a beat-up Cadillac hearse that was missing hubcaps, in a box (I cannot call it a casket, even in the loosest sense of the word) that was upholstered in and out with what looked like gray speaker-box felt. It was almost comically sad.

The end of someone’s life is no laughing matter, but I couldn’t help but wonder and smirk about what divine wrath he must have incurred for the last party to be so fucking sad.

There were stories about Uncle Gerald being a successful insurance broker in his prime. Having a nice house, lots of money, and cool cars. There were photos of him in awful suits that looked like couch upholstery patterns and wide butterfly collars. Suits which I am sure they were the height of luxury in the 70’s but those things rarely age well. I can’t picture it, but I would imagine it to be true.

It’s tough for me to say where things fell off for him, but I know that things never got better for him, either. Gerald had a son, Little Jerry, who killed himself in his bedroom when he was 18. I was 8 when that happened. I don’t remember him well, I only recall seeing him smiling at me occasionally at family functions and saying, “what’s up little Fe!?” in an excited voice when he would see me. He dressed the way that hair metal bands dressed, ripped jeans and leather jackets and big hair. Lively, sweet, and ultimately doomed.

I recall visiting the senior Gerald with my mom and dad just a day or so after his son’s death. We walked around the apartment and his room. His other child, Renee, telling us about the pressure that their dad put on him to be “successful”. Hammering on him for reading magazines about metal music, rather than newspapers. One day, little Jerry had had enough. She showed us the dark spot on the dark carpet where he lay, bleeding to death. Music so loud that even in the next room they couldn’t hear the noises.

During Little Jerry’s funeral, a sizeable number of the attendees were falling-down drunk, and in their grief, decided that a closed casket was unacceptable. Working graveside to open it to view their loved one, who had several days prior shot himself in the mouth with a shotgun. My Dad’s sister Peggy, sober, carefully attempting to control the chaos, used a Kleenex to wipe some of the many layers of garish makeup off his face.

A small gesture of grace in a most ungraceful situation.

We walk just a few short blocks, and we arrive that the door of my aunt Rita. She lived in some rowhouse across the street from the old Mile High Stadium.

The fact that she was that close to us, and I had no idea, was truly symbolic of the relationship that my parents had with one another’s family.

She opens the door for us and lets us in. Her and my dad talk together in the tiny apartment kitchen, and I sit on the couch, not paying attention. Trying not to pay attention. After a few moments, I look over and watch my dad reach for a handle of McCormick’s vodka that’s sitting on her table. He pours some into a red cup with orange juice and swishes it around, and then just as quickly, slams it. He quickly looks over at me and I look away, pretending to not see.

I recall this specific moment vividly, because this was the first time that I remember seeing my dad drink while knowing that he shouldn’t. Knowing that everything was on the line and what it actually meant to see him give that up. One small step for an alcoholic, one giant leap back into the beast.

When you’re young you don’t realize that these things are problems until one day you do. And then you dread them. They become the monster that steals your comfort and your normalcy. They become the shadow of the earth, chasing away the day and bringing a very long night. You never blame the person, only the drink. Until one day it switches, and it never goes back. And for a young boy, who had finally gotten his dad back home, the contents of that red cup were the catalyst to unravel everything that we had worked for.

My dad wasn’t a social drinker. When he did drink, it was with the urgency and purpose that we consume oxygen with. This wasn’t a casual cocktail with his sister, it was the shifting of tectonic plates. That drink was a fracture that would eventually rip us apart again. Again.

I sat there paralyzed. I didn’t want to be there. I wanted to be with my mom. To tell her, so she could tell him to stop. I wanted to be anywhere but that fucking couch. My skin was crawling, and I wanted to bawl like a baby and tell him to stop. As he mentioned my name, I would look over, he would be looking at me to respond to some question. I couldn’t look him in the eyes. I tried hard to play off the disappointment, but much like my mother, I tended to wear my disdain for people right across my face.

We got up to leave and relief washed over me. Maybe this was it. We would go home and listen to music, and this would be our secret. We would wait for mom to get off work and then we would go to grandmas to open gifts, and this never happened. My world was intact, limping, but intact. Without even mentioning it, he was asking me to lie to my mom and I would have happily done so, if it meant keeping this domestic bliss-train rolling. Partners aren’t the only ones who do crazy things for love.

The relief that I felt faded quickly as we walked past the block to turn towards our house.

We were going to Gerald’s after all.

And even at this point, I knew what the rest of the night would look like.

We walked into the house that Gerald was living in. A carriage house that sat on top of a garage next to a piece of shit house, which, when compared to the glorified treehouse he was in, seemed almost like a mansion. Inside, the drinking only continued steadily, almost like making up for lost time.

During his prison term, the few visits that I had were always colored with the promises of how amazing things would be when he got out. All the things that we would do and see and take part in. How he was “done with the bullshit”, as he always put it. Highlighting again and again that from now on, he was choosing us. This particular phrase always made me ask why he never chose us before.

As I watched him, my senses were awash with anger and disappointment. I knew what my mom would say. The longer that I sat there, the more I felt like I would be in trouble as well. So, I pretended to walk outside for some air. As soon as I did, I bolted down the stairs and jumped the fence. I can still recall the immense fear that ran through my spine. I felt like I was running in molasses. Like the nightmares where you can’t run fast enough or punch with any force.

I could hear my dad scream behind me “Felix, get back here NOW!”. Fearing his wrath should he catch me; I sprinted like a gazelle through the yard and over the chain-link hurdle. Not an athlete in the classical sense, or any sense whatsoever, I imagine this epic dash looked less like a gazelle and more like a refrigerator jogging and then fat-ly trying to hop a fence. Despite my lack of athletic prowess, I managed to escape a large, out of shape, angry man who had made zero attempt to physically enforce his demand.

I didn’t see him until several hours later. He showed up drunk to my maternal grandparent’s house for the Christmas Eve party we had there every year. I was chest-deep in a feeling that I can’t quite name, but it’s a potent mix between anger, fear, and disappointment.

Several hours after that, we were back home. I sat on my bed with my brand new discman that my parents had gotten me for Christmas. Two fresh, new CD’s came with the gift, neatly bundled in the wrapping paper. Two albums that I wasn’t particularly into, but the comfort of such a rare novelty felt good. I put the thick, foam-padded headphones over my ears and drowned out very loud, very hateful argument that my parents were having.

I don’t recall much of what happened in the next few months in that duplex. However, I can venture a very certain guess. They fought, and he left. He would stay somewhere with people that we didn’t know, and he would drink until he literally couldn’t function. The next day, he would be in such bad shape that the only way to deal with the excruciating pain of the hangover he had would be to chase it away with another bottle of whatever. Usually cheap vodka. It would help, but it meant that he was now saddled with the burden of maintaining, and that meant that his momentary lapse in judgement would ultimately last for weeks or months.

There was usually an event, like being asked to leave after he had worn out his welcome, or a fight, or a short trip to jail that would put the brakes on it. Then the calls to us would start. Letters. Pleading. Apologizing. Begging. Most often, I would be the Trojan Horse. He would play my sympathy and ultimately use that as a means to come back home. I imagine dads and families do this all the time. “I just want to see my kids” would turn into spending the night, and then the silent shift back into another episode of our favorite sitcom, Marital Normalcy.

The memories that I do have of that era are all of very brief moments from middle school, dotted with certain events that stick out for one reason or another. There is a great deal of these that involve my father. Mostly doing normal, fatherly things. Those are my favorites.

Like a VH1 show about some irrelevant decade, the early 90’s as they exist in my mind can be linked together with the same pop-bullshit milestones that dot the psyche of anyone reaching puberty in that era. Lowrider bikes. The OJ trial. Jurassic Park release. Kurt Cobain’s suicide. Beavis and Butthead, Fucking Wonderwall. Each one of these can be bookended with moments that I spent actually growing up. Not terribly bad. Not terribly good.

My friends all had dads that worked night shifts but still woke up early. Dad’s that spent the weekend with them. Put them into little league, maybe even coached them. Or they worked on the yard. They took fishing trips. They had dads that showed up to events at schools, who paid attention to what they were doing in school. Dads who took part in parent-teacher conferences and followed-up with the advice of the teachers. I also had friends whose father’s beat them to within an inch of their lives. It’s a spectrum.

Earlier in the year, I had received an assignment at school as part of detention for being rowdy in class; I was going to be the MC at the school talent show. I think the intent was for there to be some justice that my teacher thought they would deliver with this, you-want-attention-so-bad-here-it-fucking-is, kind of method, but secretly, I loved it. I didn’t really practice; I just needed the microphone and a spotlight. Two things that I can’t turn down to this very day.

I invited my parents, to showcase this “achievement” of mine, and this, unlike many, many other school events, was one that my father actually attended. One of the acts was a young girl, who was very overweight, singing a poem in Spanish about her guitar. On stage in front of the court of middle school judgement, baring her soul, she gracefully sang the words “I love my guitar. I strum my guitar…”. Starting on the ride home, and for the rest of the evening, my dad in a low-pitched, mocking voice singing “Yo comi mi guitarra”, which, in Spanish means: I ate my guitar. The sentimental piece was always lost with my father. Either that, or the humor was more important than the symbolism.

It was never a given that he should take part in that part of my life. It was a duty that was more a product of bad timing than actual interest on his part. To this day, it doesn’t bother me because I understand my father much more as I would a friend now than as parent. He became a father before he became a man in the sense that he never had much use for the symbolic or the sentimental, nor did he have a roadmap to follow, as his father was never really around. Uncle Gerald was the closest analog to a father, and, well, you know how that goes.

Flash forward 20 something years from the room with the Slayer posters and the discman. It’s 2018. Christmas Eve. The same living room in the same old house that I had ran to as a child on this same night. This time, I drove to it with my wife and kids. My Dad is there, waiting to see us. A few weeks back, my mom had started talking with him again.

Since the method of using the kids to regain her trust didn’t work when the kids are now adults, he started calling my grandmother. She was always very good to him. She referred to herself as the mother he gained when he lost his. He would call just to “see how you’re doing” hoping that he could talk to my mom in some capacity. This trick would work over and over, but this time, it wasn’t. At least, until he told my grandmother that he had gone to the doctor recently and found out he had advanced cirrhosis, brought to his attention by his most recent binges, which, after his death, I have learned were some of the most severe of his lifetime. The shock of hearing it got my mom immediately on the phone. In the few weeks prior to Christmas, he had begun staying with them again. Struggling to get around and mostly spent in bed.

For years, my mother and I played this unspoken game where one of us would eventually fall back into his web and start talking to him again. There was always a sense of relief when we reconciled, and both came to grips with him being back. We never really talked about how we felt, ever. We just did things and then lived in a quiet anxiety. That’s what the most of my life was like with those two.

My dad was a big guy. Around 250 pounds. 6’2”. So, I was taken completely aback when I walked into the living room to see him sitting on the recliner. He was grayish-yellow. Small in every way except his belly, which was large and almost distended. He could barely lift his eyes to meet mine, but he got up and did his best to hug me anyway.

Somehow, around my dad, I had this habit of morphing back into the 8-year-old boy that had to tell him EVERY good thing that had happened to me. It used to be a dissertation on the Ninja Turtles. Now it’s about helping to build a business. In both cases, my eyes light up and my skin gets a chill with excitement. I needed the praise and I needed to see the pride across his face. This time was no different, except with a bit more restraint.

We talked about me and then we talked about him. He told me a story about some remodeling work that he had done for some Chinese guy, and how the guy was refusing to pay because he didn’t have a permit for the work. Truth be told, I didn’t really understand what he was telling me, and at the time I chalked that up to my attention being split with the rush of the kids struggling to contain their excitement at opening gifts and his slow and quiet retelling.

A few days later, waiting in the ER before he was moved to the ICU, a nurse told me that this was a major symptom of advanced cirrhosis, deep confusion. The damage that alcohol had done to his brain was significant, and for some reason, for all that I knew alcohol would destroy, it never occurred to me that it would hurt his brain. I took the information and sat with it. I didn’t really think beyond that, other than to hope what I was saying made sense to him. I wondered for second if as we sat and talked, that he could have been just as confused as me, and that thought broke my heart into pieces.

We closed that night with hugs and what I feel was an unspoken apology for everything that had happened. I wanted to believe that we somehow closed the Christmas Eve disaster loop that started with him and that fucking red solo cup and ended with him a few days from death from everything inside it, but I tend to make things too symbolic.

I knew that he was scared. He said as much to my mom. He didn’t want to die this way. It wasn’t the way his story was supposed to end. Afterwards, that hug and those moments, I wanted to believe that there was some penance in it for him. I don’t know if that’s true and to this day I wonder if it was him that was taking from the cup or the cup taking from him.

For years, I thought it was the anger about the unfairness of it all. That some people could just have a normal fucking life, with a parent who didn’t do things like this. That some kids didn’t have to dread these nights and the fear that bubbles up when you start to understand the impact these moments have. But looking back now, I didn’t know any better. I couldn’t really see the better reality to know that mine wasn’t so good. However, as you get older and you see more, and maybe you come of age in the dot-com era, you start to see status. You get to see what things may have been like. You get a girlfriend that comes from some money and the contrast becomes clear: you weren’t dealt a very good hand.

Those are moments that define the path that people eventually take. Life delivers on a silver platter a big fat fucking excuse to not make something of themselves. A dartboard to constantly throw their failures at. And believe you me, it’s easy.

As anyone born in the Venn diagram overlap of being Chicano and Catholic can tell you, there’s always a reason to feel like you don’t deserve something. You pair that feeling with the fact that you don’t have a pedigree that you come from, you don’t have money, you don’t have status, you don’t have a house, you haven’t traveled, you haven’t vacationed, you haven’t had consistent medical or dental care, you’re “too American for the Mexicans and too Mexican for the Americans” as the quote goes, and it gets pretty easy to talk yourself out of just about anything. You grow up with an intense aversion to making anyone mad, you evolve unique senses and skills, ways to negotiate, to put yourself on the same ground as the people you are interacting with. You lie about things you like and dislike. You tell people that you think traveling is stupid because you’ve never been able to leave 26th avenue.

I used to think that dessert was something that people ate only in movies and TV. And I would lie about eating it. Casually bringing up in conversation that we had dessert after dinner as if it were some ticket to the Convention of Normal Families. Nothing to see here, folks. I am normal just like you are. Not better either, but equal. The dessert story is not to say we didn’t eat sweets and cake and ice cream occasionally, but the idea of mom cleaning up dinner and then dishing out a small bowls of sorbet seemed so cheesy and Leave-It-To-Beaver, but I still imagined the rest of the normal world taking part in this silly ceremony, therefore, I would represent that we were, too.

You settle into a pattern of accepting what life hands you and finding the anger bubble up at every single crevice you want to look. You develop a confirmation bias that says “see, I fucking KNEW it” when something doesn’t go your way, and you tend to overlook your part in creating that issue, because you always feel like you deserve a little more wiggle room when you don’t catch a break that you didn’t work for. When you show up a few minutes late for work and you get written up. When you spend all of your money, and you don’t have enough gas to go to work or to go out, after all, you had it worse, right? And of course, you’re right, obviously. You have this deep, cold, well of bad experiences to draw from. And as a young man in a bad neighborhood in big public schools, there’s no shortage of teachers and aides, who, with the best intentions in the world, confirm for you, that you’re right: Your life fucking sucks.

But maybe it doesn’t.

Maybe you don’t end up destitute or impoverished. You end up with a fine life filled with purpose and meaning. A life in which you gain access to some capital which you leverage to improve the situation for you and your family. You don’t use the adage that “it was good enough for me” with your kids. You aren’t wealthy, but you’ve stepped up far enough on the social ladder to put your kids in a better environment to learn and to grow and improve theirs. Removed from the violence and grime that you grew up with. Removed from the culture of dependency that you grew up in. Bussing to and from government offices and free clinics. Free from WIC and food stamps. Free from the hunger that would wake you up at night and force you to sneak into the kitchen to eat whatever you could find or drink a lot of water to feel full. Removed from the fear of living in tight apartment complexes with drug addicts and criminals keeping you awake. The exposure to the naked face of death, the bleeding edges of society.

At a tender age, you sit outside on a cold concrete stoop and you stare at the shimmering glass city in the distance. From the bad part of the city, it doesn’t look like cold glass and steel. It looks like heaven. The lights and gleaming stainless-steel hands reaching into the air look like a galaxy where you could be anything you wanted.

You ponder the deep stuff, the sad stuff, the path ahead of you stuff. There is a funny thing, when you read book after book of hard-luck stories of people like me, they never mention it. Seeing crying athletes and lamenting rappers tell tales of gritty streets and urban culture, they are always glossing over it. The one thing that’s missing from a life of scraping moment to moment, apartment to apartment: the concept of planning for the future. Even planning for the next day. It’s all so tactical and it’s all so necessary. Sure, there are people who imagine getting the things that they want, but nothing of the path to get there. It seems almost silly to contemplate existentialism under a streetlight. But perhaps, there are few better places.

In doing so, you arrive at a place of great comfort but also great fear. That you are officially aware of who you are. You know your paradigms and more than that, you know who you aren’t. There is power in having enough code written in you to not be okay with writing off the ails and the woes as things that have happened to you. There is no comfort in that because there is no control. And you find that after letting the world control you for so long, you are bound and determined to not give away the steering wheel from here on out. It’s up to you. The trial and the failures. You answer to them now. Not your past, or your neighborhood or your dad. It’s all you.

Perhaps there is a grander message and meaning to the story of the red solo cup, but I don’t think so. Unraveling these threads makes us feel good, but rarely do we learn more than we actually knew. Things are shitty. And shitty things happen to good people. During the writing process, I always imagine the people in the story actually reading the story and I wonder what they would think. Would they agree? I feel like I am fair, and the picture that I am painting is as clear and unembellished as I can make it. But sometimes truth is subjective and rarely do we truly separate actions from intentions, especially our own.

I can only speak for myself. I can only tell you of my own belief that what the world held for me was more than material bullshit or a life of repeating the same cycles. Right now, I have the gift of hindsight. I also have the ability to gloss over the cracks. Memory has a funny way of smoothing out the rough edges. Our own ego has a way of turning luck and happenstance into these sparkling decisions that we use to tell everyone else.

Eventually, we moved from a small brick duplex to a large brick apartment complex just before I started high school. The move wasn’t far, but it was enough to kick me out of Denver Public School district and into an adjacent district, Jefferson County. In reality, it was just a few blocks, but it might as well have been a different country. A new culture with new faces and people and a way of doing things. Mostly, it was a different ethnic group, but it was new and therefore exciting and scary at the same time.

Leaving Denver was leaving a world that was awash with gangs and violence. I wasn’t directly a part of that, but I was certainly on the periphery. There were some bad people at the center of the maelstrom and as it spun, its tentacles sucked in kids like me. I was within one degree of a lot of those people and any flavor of felonies you could imagine. Drug dealing, murder, theft, violence, vandalism, you name it. I had friends whose houses had been shot up. 15-year-old old brothers or cousins or uncles who were shot and killed in street fights and car jackings. Parents of friends and friends who were incarcerated for a great many crimes. People often wonder at the silliness of gangs and street culture; questioning how someone could actually do that. Wondering what would possess someone to flagrantly ignore their part of the social contract. How could an animal wander into such an obvious snare, they ask themselves these questions, dripping with judgment as they apply at the same college their dad went to.

What they fail to see is that you don’t make a choice as much as you grow up inside of it. You don’t really see that it’s wrong because it’s what’s normal. For most people, anyway.

There is a great illusion and mystique around power and money and the disregard for law. There is no shortage of city council members and legislators who pass laws to help these “problem” areas, without realizing that the very people they are helping can actually perpetuate the issues. The people I grew up with, both in and away from gang culture will lament at the scourge of gentrification. Fighting against the influx of “new” people into their neighborhood yet they will never turn that same skeptical gaze at the fact that none of their own people are able to leave those same neighborhoods. We hold one another down, if only to make ourselves feel better about our own station.

It’s hard to see in the moment, but from a seat that’s 25 years in the future, it’s not hard to make a case for the lack of a strong father figure leaving a generation of boys to run wild. Creating their own children without any blueprint for how to make good people.

I wasn’t above the pull of the gutter and you can buy a ticket to the show simply by wearing the clothes. Blending into the army of kids wearing Dickies pants and Chuck Taylors or Nike Cortez shoes. Oversized white T -shirts and black Locs sunglasses. Starting in elementary school, the pull was slow but steady. You wouldn’t ever really see these kids slipping down that hill unless you let some time pass, like the first day of school after summer break. We came back into 5th or 6th grade with new looks, much more severe, telling stories of our first times smoking weed or drinking or even having sex, boys pretending to be men, having left the previous school year as children who debated furiously the pros and cons of particular toys or pro football players.

That’s when the change really gets dramatic. When these boys become men and the challenges become more extreme. The testosterone flowing high at the same time we are faced with the constant need to prove ourselves as more hardcore than the next guy. Living more recklessly, drugs, sex, guns. During the time when our fathers should be lording over our every move with a watchmaker’s precision, instead, we had the unyielding voice of pop culture shoving gang life down our throats. Left to become a man under the watch of a woman, who herself was barely in her 30’s and doing her best to check the bigger boxes, like food and shelter.

Moving those few blocks perhaps saved my life.

Over the summer mom and dad had patched things up again. My dad was working for a janitorial company. He was friends with the owner and managed to secure a sweet gig as a manager who would go check on various jobs. It came with some good money, and even a vehicle. He had a grey jeep Cherokee with the logo of the company “Janitorial Unlimited” across the front set of doors. For me and my mom, it came with something even more precious: stability.

They were good at settling back into patterns, which I guess applies to both good and bad things. They were earning a double income, so life got a little easier in our bubble. A bit of room around the neck to breathe and think a little further than the next day.

As summer wound to a close, he and my mom had taken me to freshman orientation at the high school near us, Jefferson Senior. The crowd of kids my age terrified me. I felt like an enemy soldier wandering through the opposing army’s dress parade, and based on the stares that I was getting, they would have probably agreed. These kids were in cargo pants and ripped jeans. Nirvana shirts. Flannel. Ball chain necklaces. Ironically, the same Chuck Taylors I was wearing, but laced too tightly, and filthy, ink scribbled on them.

After orientation, we went to grab a bite. Over dinner, my parents asked if I was excited. I answered yes, of course. And I was. I talked to them about trying out for the football team, which in hindsight, what the fuck. The idea seemed to bring a smile to my dad’s face, so I continued pressing it.

There was a relief that I couldn’t really describe back then, but now realize that image I was walking around with wasn’t really me. It was more of a shield, if anything, and dropping it felt amazing. The memories that I have of that time are always colored the deep orange of an August sunset. I can smell the trees and hear the cicadas buzzing. A period of calm and peace bookended by chaos and violence. Not the bloody, tv kind, but the quiet kind that chips away at you. The kind that you hide when you walk out of the house the next day.

I went to sleep the night of high school orientation with an optimism that was entirely new to me. One that kids from my neighborhood don’t usually get to feel.

I slept with it over me like a warm blanket.